How the Pwnedlist Got Pwned

Last week, I learned about a vulnerability that exposed all 866 million account credentials harvested by pwnedlist.com, a service designed to help companies track public password breaches that may create security problems for their users. The vulnerability has since been fixed, but this simple security flaw may have inadvertently exacerbated countless breaches by preserving the data lost in them and then providing free access to one of the Internet’s largest collections of compromised credentials.

Pwnedlist is run by Scottsdale, Ariz. based InfoArmor, and is marketed as a repository of usernames and passwords that have been publicly leaked online for any period of time at Pastebin, online chat channels and other free data dump sites.

Pwnedlist is run by Scottsdale, Ariz. based InfoArmor, and is marketed as a repository of usernames and passwords that have been publicly leaked online for any period of time at Pastebin, online chat channels and other free data dump sites.

The service until quite recently was free to all comers, but it makes money by allowing companies to get a live feed of usernames and passwords exposed in third-party breaches which might create security problems going forward for the subscriber organization and its employees.

This 2014 article from the Phoenix Business Journal describes one way InfoArmor markets the Pwnedlist to companies: “InfoArmor’s new Vendor Security Monitoring tool allows businesses to do due diligence and monitor its third-party vendors through real-time safety reports.”

The trouble is, the way Pwnedlist should work is very different from how it does. This became evident after I was contacted by Bob Hodges, a longtime reader and security researcher in Detroit who discovered something peculiar while he was using Pwnedlist: Hodges wanted to add to his watchlist the .edu and .com domains for which he is the administrator, but that feature wasn’t available.

In the first sign that something wasn’t quite right authentication-wise at Pwnedlist, the system didn’t even allow him to validate that he had control of an email address or domain by sending him a verification to said email or domain.

On the other hand, he found he could monitor any email address he wanted. Hodges said this gave him an idea about how to add his domains: Turns out that when any Pwnedlist user requests that a new Web site name be added to his “Watchlist,” the process for approving that request was fundamentally flawed.

That’s because the process of adding a new thing for Pwnedlist to look for — be it a domain, email address, or password hash — was a two-step procedure involving a submit button and confirmation page, and the confirmation page didn’t bother to check whether the thing being added in the first step was the same as the thing approved in the confirmation page. [For the Geek Factor 5 crowd here, this vulnerability type is known as “parameter tampering,” and it involves the ability to modify hidden POST requests].

“Their system is supposed to compare the data that gets submitted in the second step with what you initially submitted in the first window, but there’s nothing to prevent you from changing that,” Hodges said. “They’re not even checking normal email addresses. For example, when you add an email to your watchlist, that email [account] doesn’t get a message saying they’ve been added. After you add an email you don’t own or control, it gives you the verified check box, but in reality it does no verification. You just typed it in. It’s almost like at some point they just disabled any verification systems they may have had at Pwnedlist.”

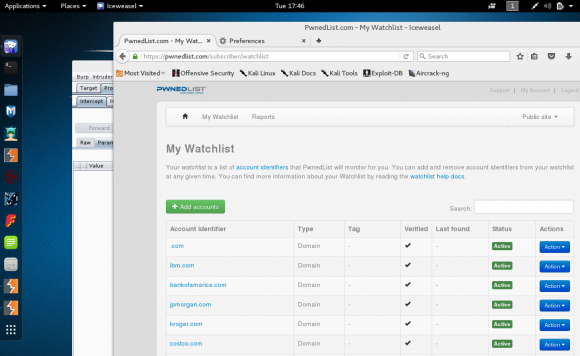

Hodges explained that one could easily circumvent Pwnedlist’s account controls by downloading and running a copy of Kali Linux — a free suite of tools made for finding and exploiting software and network vulnerabilities.

Always the student, I wanted to see this first-hand. I had a Pwnedlist account from way back when it first launched in 2011, so I fired up a downloadable virtual version of Kali on top of the free VirtualBox platform on my Mac. Kali comes with a pretty handy vulnerability scanner called Burpsuite, which makes sniffing, snarfing and otherwise tampering with traffic to and from Web sites a fairly straightforward point-and-click exercise.

Indeed, after about a minute of instruction, I was able to replicate Hodges’ findings, successfully adding Apple.com to my watchlist. I also found I could add basically any resource I wanted. Although I verified that I could add top-level domains like “.com” and “.net,” I did not run these queries because I suspected that doing so would crash the database, and in any case might call unwanted attention to my account. (I also resisted the strong temptation to simply shut up about this bug and use it as my own private breach alerting service for the Fortune 500 firms).

Hodges told me that any newly-added domains would take about 24 hours to populate with results. But for some reason my account was taking far longer. Then I noticed that the email address I’d used to sign up for the free account back in 2011 didn’t have any hits in the Pwnedlist, and that was simply not possible if Pwnedlist was doing a halfway decent job tracking breaches. So I pinged InfoArmor and asked them to check my account. Sure enough, they said, it had never been used and was long ago deactivated.

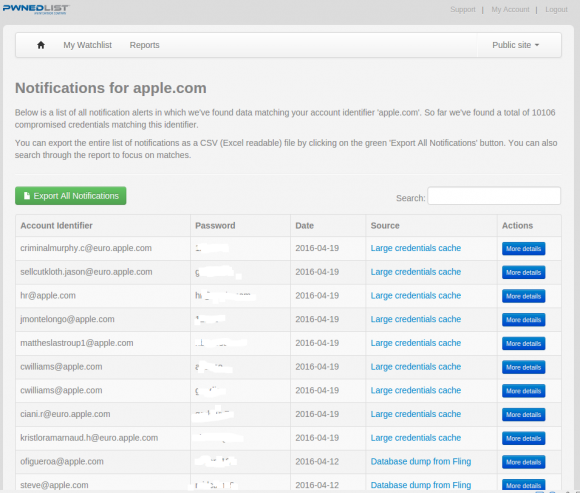

Less than 12 hours after InfoArmor revived my dormant account, I received an automated email alert from the Pwnedlist telling me I had new results for Apple.com. In fact, the report I was then able to download included more than 100,000 usernames and passwords for accounts ending in apple.com. The data was available in plain text, and downloadable as a spreadsheet.

Some of the more than 100,000 credentials that Pwnedlist returned for me in a report on all passwords tied to email addresses that include “apple.com”.

It took a while for the enormity of what had just happened to sink in. I could now effectively request a report including all 866 million account credentials recorded by the Pwnsedlist. In short, the Pwnedlist had been pwned.

At this point, I got back in touch with InfoArmor and told them what Hodges had found and shown me. Their first response was that somehow I been given a privileged account on Pwnedlist, and that this is what allowed me to add any domain I chose. After all, I’d added the top 20 companies in the Fortune 500. How had I been able to do that?

“The account type you had had more privileges than than an ordinary user would,” insisted Pwnedlist founder Alen Puzic.

After validating the bug, I added some other domains just for giggles. I deleted them all (except the Apple one) before they could generate reports.

I doubted that was true, and I suspected the vulnerability was present across their system regardless of which account type was used. Puzic said the company stopped allowing free account signups about six months ago, but since I had him on the phone I suggested he create a new, free account just for our testing purposes.

He rather gamely agreed. Within 30 seconds after the account was activated, I was able to add “gmail.com” to my Pwnedlist watchlist. Had we given it enough time, that query almost certainly would have caused Pwnedlist to produce a report with tens of millions of compromised credentials involving Gmail accounts.

“Wow, so you really can add whatever domain you want,” Puzic said in amazement as he loaded and viewed my account on his end.

Pwnedlist.com went offline shortly after my phonecall with InfoArmor.

It’s a shame that InfoArmor couldn’t design better authorization and authentication systems for Pwnedlist, given that the service itself is a monument to object failures in that regard. I’m a big believer in companies getting better intelligence about how large-scale everyday password breaches may impact their security, but it helps no one when a service that catalogs breaches has a lame security weakness that potentially prolongs and exacerbates them.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.