French Firms Rocked by Kasbah Hacker?

A large number of French critical infrastructure firms were hacked as part of an extended malware campaign that appears to have been orchestrated by at least one attacker based in Morocco, KrebsOnSecurity has learned. An individual thought to be involved has earned accolades from the likes of Apple, Dell, and Microsoft for helping to find and fix security vulnerabilities in their products.

In 2018, security intelligence firm HYAS discovered a malware network communicating with systems inside of a French national power company. The malware was identified as a version of the remote access trojan (RAT) known as njRAT, which has been used against millions of targets globally with a focus on victims in the Middle East.

Further investigation revealed the electricity provider was just one of many French critical infrastructure firms that had systems beaconing home to the malware network’s control center.

Other victims included one of France’s largest hospital systems; a French automobile manufacturer; a major French bank; companies that work with or manage networks for French postal and transportation systems; a domestic firm that operates a number of airports in France; a state-owned railway company; and multiple nuclear research facilities.

HYAS said it quickly notified the French national computer emergency team and the FBI about its findings, which pointed to a dynamic domain name system (DNS) provider on which the purveyors of this attack campaign relied for their various malware servers.

When it didn’t hear from French authorities after almost a week, HYAS asked the dynamic DNS provider to “sinkhole” the malware network’s control servers. Sinkholing is a practice by which researchers assume control over a malware network’s domains, redirecting any traffic flowing to those systems to a server the researchers control.

While sinkholing doesn’t clean up infected systems, it can prevent the attackers from continuing to harvest data from infected PCs or sending them new commands and malware updates. HYAS found that despite its notifications to the French authorities, some of the apparently infected systems were still attempting to contact the sinkholed control networks up until late 2019.

“Due to our remote visibility it is impossible for us to determine if the malware infections have been contained within the [affected] organizations,” HYAS wrote in a report summarizing their findings. “It is possible that an infected computer is beaconing, but is unable to egress to the command and control due to outbound firewall restrictions.”

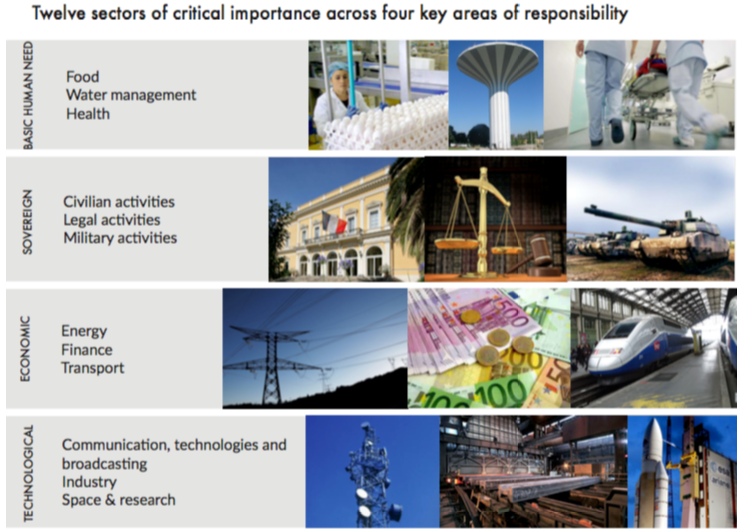

About the only French critical infrastructure vertical not touched by the Kasbah hackers was the water management sector.

HYAS said given the entities compromised — and that only a handful of known compromises occurred outside of France — there’s a strong possibility this was the result of an orchestrated phishing campaign targeting French infrastructure firms. It also concluded the domains associated with this campaign were very likely controlled by a group of adversaries based in Morocco.

“What caught our attention was the nature of the victims and the fact that there were no other observed compromises outside of France,” said Sasha Angus, vice president of intelligence for HYAS. “With the exception of water management, when looking at the organizations involved, each fell within one of the verticals in France’s critical infrastructure strategic plan. While we couldn’t rule out financial crime as the actor’s potential motive, it didn’t appear that the actor leveraged any normal financial crime tools.”

‘FATAL’ ERROR

HYAS said the dynamic DNS provider shared information showing that one of the email addresses used to register a key DNS server for the malware network was tied to a domain for a legitimate business based in Morocco.

According to historic records maintained by Domaintools.com [an advertiser on this site], that email address —

Archived copies of talainine.com indicate the business was managed by two individuals, including someone named Yassine Algangaf. A Google search for that name reveals a similarly named individual has been credited by a number of major software companies — including Apple, Dell and Microsoft — with reporting security vulnerabilities in their products.

A search on this name at Facebook turned up a page for another now-defunct business called Yamosoft.com that lists Algangaf as an owner. A cached copy of Yamosoft.com at archive.org says it was a Moroccan computer security service that specialized in security audits, computer hacking investigations, penetration testing and source code review.

A search on the

A LinkedIn profile for a Yassine Algangaf says he’s a penetration tester from the Guelmim province of Morocco. Yet another LinkedIn profile under the same name and location says he is a freelance programmer and penetration tester. Both profiles include the phrase “attack prevention mechanisms researcher security tools proof of concepts developer” in the description of the user’s job experience.

Searching for this phrase in Google turns up another Facebook page, this time for a “Yassine Majidi,” under the profile name “FatalW01.” A review of Majidi’s Facebook profile shows that phrase as his tag line, and that he has signed several of his posts over the years as “Fatal.001.”

There are also two different Skype accounts registered to the ing.equipepro.com email address, one for Yassine Majidi and another for Yassine Algangaf. There is a third Skype account nicknamed “Fatal.001” that is tied to the same phone number included on talainine.com as a contact number for Yassine Algangaf (+212611604438). A video on Majidi’s Facebook page shows him logged in to the “Fatal.001” Skype account.

On his Facebook profile, Majidi includes screen shots of several emails from software companies thanking him for reporting vulnerabilities in their products. Fatal.001 was an active member on dev-point[.]com, an Arabic-language computer hacking forum. Throughout multiple posts, Fatal.001 discusses his work in developing spam tools and RAT malware.

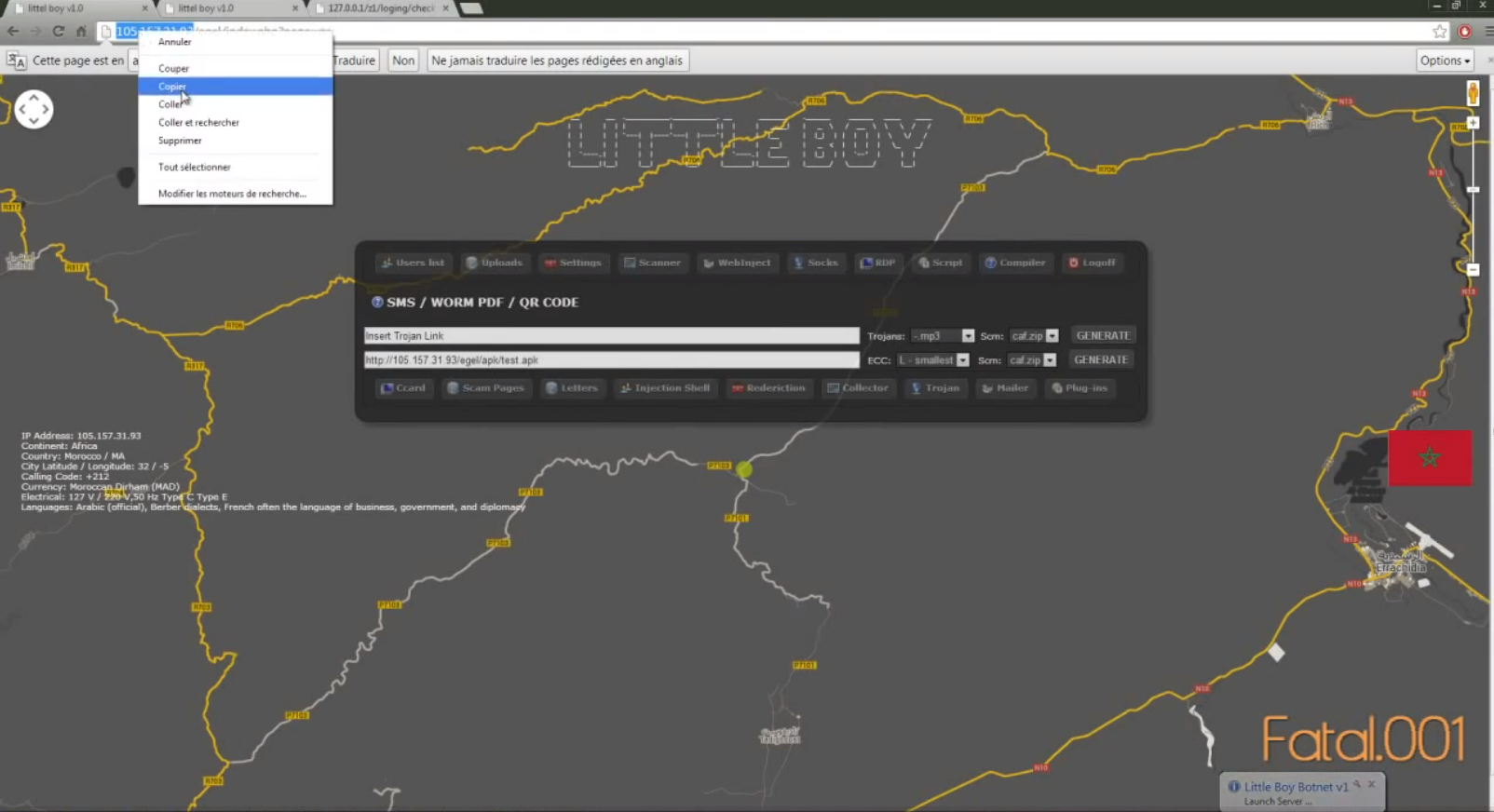

In this two-hour Arabic language YouTube tutorial from 2014, Fatal.001 explains how to use a RAT he developed called “Little Boy” to steal credit card numbers and passwords from victims. The main control screen for the Little Boy botnet interface includes a map of Morocco.

Reached via LinkedIn, Algangaf confirmed he used the pseudonyms Majidi and Fatal.001 for his security research and bug hunting. But he denied ever participating in illegal hacking activities. He acknowledged that

“It has already been hacked and recovered after a certain period,” Algangaf said. “Since I am a security researcher, I publish from time to time a set of blogs aimed at raising awareness of potential security risks.”

As for the notion that he has somehow been developing hacking programs for years, Algangaf says this, also, is untrue. He said he never sold any copies of the Little Boy botnet, and that this was one of several tools he created for raising awareness.

“In 2013, I developed a platform for security research through which penetration test can be done for phones and computers,” Algangaf said. “It contained concepts that could benefit from a controlled domain. As for the fact that unlawful attacks were carried out on others, it is impossible because I simply have no interest in blackhat [activities].”

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.