For 2nd Time in 3 Years, Mobile Spyware Maker mSpy Leaks Millions of Sensitive Records

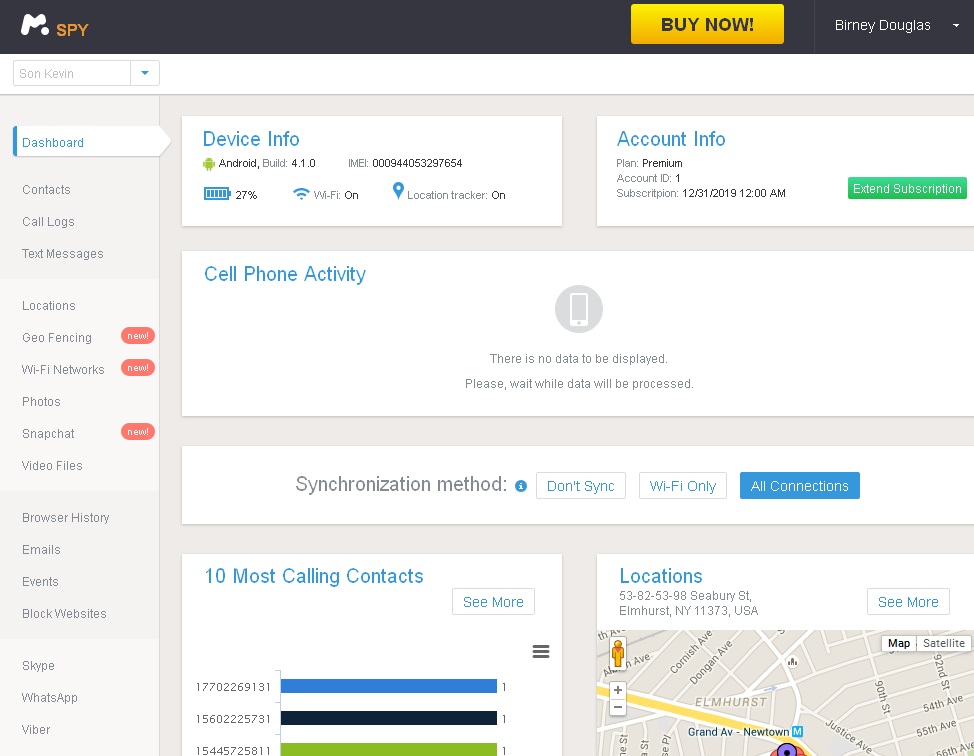

mSpy, the makers of a software-as-a-service product that claims to help more than a million paying customers spy on the mobile devices of their kids and partners, has leaked millions of sensitive records online, including passwords, call logs, text messages, contacts, notes and location data secretly collected from phones running the stealthy spyware.

Less than a week ago, security researcher Nitish Shah directed KrebsOnSecurity to an open database on the Web that allowed anyone to query up-to-the-minute mSpy records for both customer transactions at mSpy’s site and for mobile phone data collected by mSpy’s software. The database required no authentication.

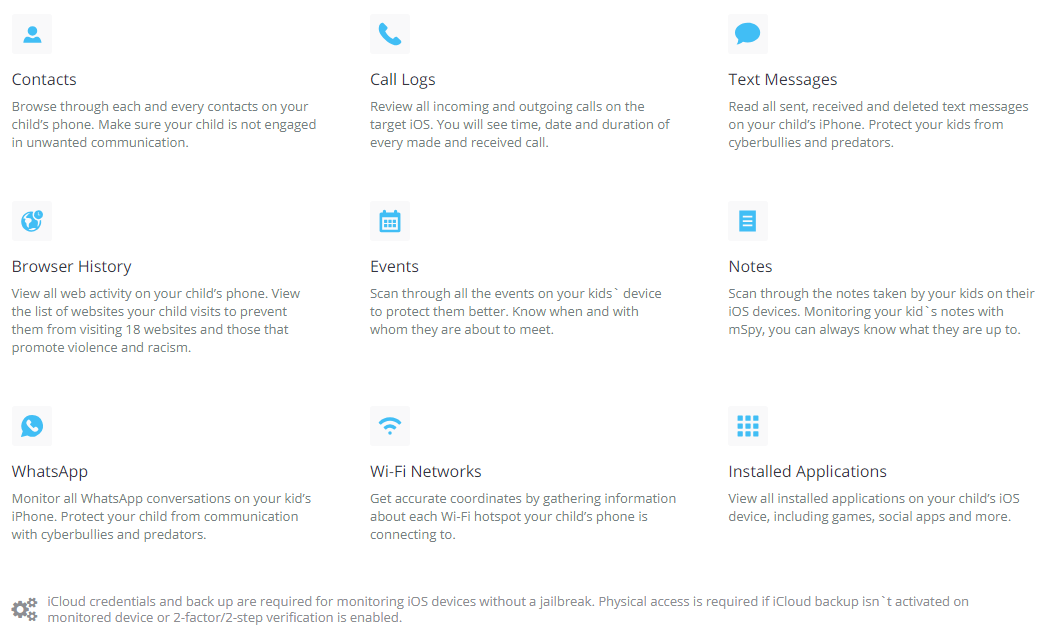

A list of data points that can be slurped from a mobile device that is secretly running mSpy’s software.

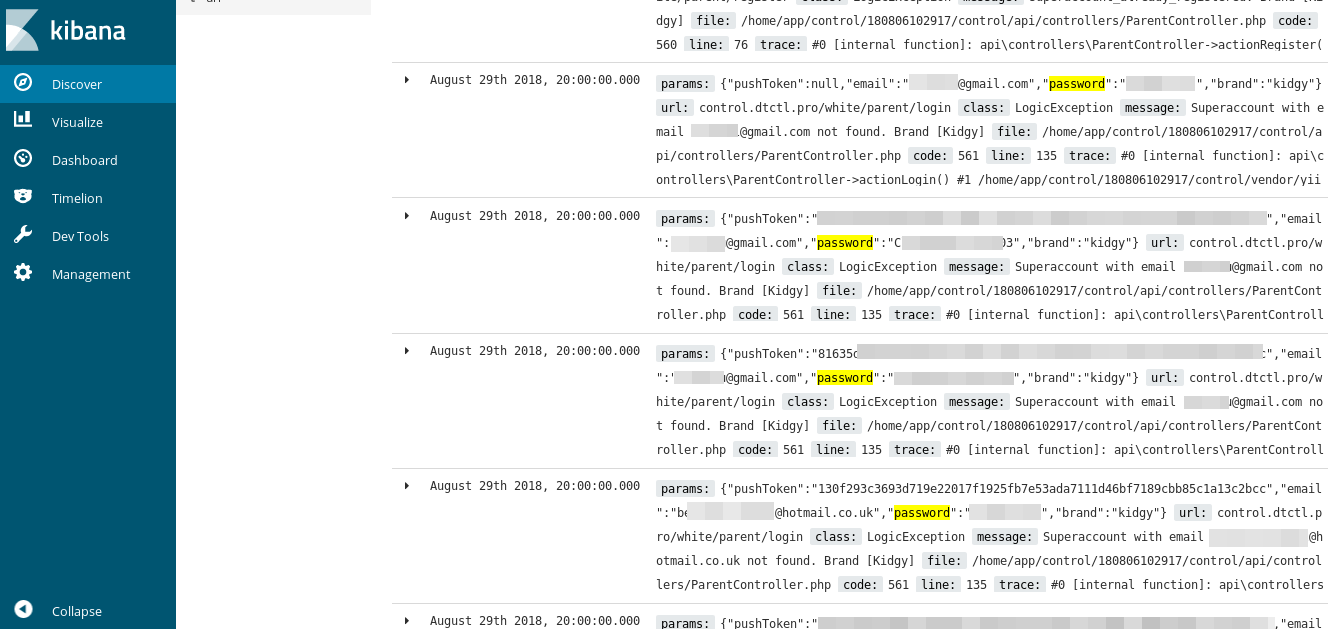

Before it was taken offline sometime in the past 12 hours, the database contained millions of records, including the username, password and private encryption key of each mSpy customer who logged in to the mSpy site or purchased an mSpy license over the past six months. The private key would allow anyone to track and view details of a mobile device running the software, Shah said.

In addition, the database included the Apple iCloud username and authentication token of mobile devices running mSpy, and what appear to be references to iCloud backup files. Anyone who stumbled upon this database also would have been able to browse the Whatsapp and Facebook messages uploaded from mobile devices equipped with mSpy.

Usernames, passwords, text messages and loads of other more personal details were leaked from mobile devices running mSpy.

Other records exposed included the transaction details of all mSpy licenses purchased over the last six months, including customer name, email address, mailing address and amount paid. Also in the data set were mSpy user logs — including the browser and Internet address information of people visiting the mSpy Web site.

Shah said when he tried to alert mSpy of his findings, the company’s support personnel ignored him.

“I was chatting with their live support, until they blocked me when I asked them to get me in contact with their CTO or head of security,” Shah said.

KrebsOnSecurity alerted mSpy about the exposed database on Aug. 30. This morning I received an email from mSpy’s chief security officer, who gave only his first name, “Andrew.”

“We have been working hard to secure our system from any possible leaks, attacks, and private information disclosure,” Andrew wrote. “All our customers’ accounts are securely encrypted and the data is being wiped out once in a short period of time. Thanks to you we have prevented this possible breach and from what we could discover the data you are talking about could be some amount of customers’ emails and possibly some other data. However, we could only find that there were only a few points of access and activity with the data.”

Some of those “points of access” were mine. In fact, because mSpy’s Web site access logs were leaked I could view evidence of my own activity on their site in real-time via the exposed database, as could Shah of his own poking around.

WHO IS MSPY?

mSpy has a history of failing to protect data about its customers and — just as critically — data secretly collected from mobile devices being spied upon by its software. In May 2015, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that mSpy had been hacked and its customer data posted to the Dark Web.

At the time, mSpy initially denied suffering a breach for more than a week, even as many of its paying customers confirmed that their information was included in the mSpy database uploaded to the Dark Web. mSpy later acknowledged a breach to the BBC, saying it had been the victim of a “predatory attack” by blackmailers, and that the company had not given in to demands for money.

mSpy pledged to redouble its security efforts in the wake of the 2015 breach. But more than two weeks after news of the 2015 mSpy breach broke, the company still had not disabled links to countless screenshots on its servers that were taken from mobile devices running mSpy.

Mspy users can track Android and iPhone users, snoop on apps like Snapchat and Skype, and keep a record of everything the target does with his or her phone.

It’s unclear exactly where mSpy is based; the company’s Web site suggests it has offices in the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom, although the firm does not appear to list an official physical address. However, according to historic Web site registration records, the company is tied to a now-defunct firm called MTechnology LTD out of the United Kingdom.

Documents obtained from Companies House, an official register of corporations in the U.K., indicate that the two founding members of the company are self-described programmers Aleksey Fedorchuk and Pavel Daletski. Those records (PDF) indicate that Daletski is a British citizen, and that Mr. Fedorchuk is from Russia. Neither men could be reached for comment.

Court documents (PDF) obtained from the U.S. District Court in Jacksonville, Fla. regarding a trademark dispute involving mSpy and Daletski state that mSpy has a U.S.-based address of 800 West El Camino Real, in Mountain View, Calif. Those same court documents indicate that Daletski is a director at a firm based in the Seychelles called Bitex Group LTD. Interestingly, that lawsuit was brought by Retina-X Studios, an mSpy competitor based in Jacksonville, Fla. that makes a product called MobileSpy.

The latest mSpy security lapse comes days after a hacker reportedly broke into the servers of TheTruthSpy — another mobile spyware-as-a-service company — and stole logins, audio recordings, pictures and text messages from mobile devices running the software.

U.S. regulators and law enforcers have taken a dim view of companies that offer mobile spyware services like mSpy. In September 2014, U.S. authorities arrested a 31-year-old Hammad Akbar, the CEO of a Lahore-based company that makes a spyware app called StealthGenie. The FBI noted that while the company advertised StealthGenie’s use for “monitoring employees and loved ones such as children,” the primary target audience was people who thought their partners were cheating. Akbar was charged with selling and advertising wiretapping equipment.

“Advertising and selling spyware technology is a criminal offense, and such conduct will be aggressively pursued by this office and our law enforcement partners,” U.S. Attorney Dana Boente said in a press release tied to Akbar’s indictment.

Akbar pleaded guilty to the charges in November 2014, and according to the Justice Department he is “the first-ever person to admit criminal activity in advertising and selling spyware that invades an unwitting victim’s confidential communications.”

A public relations pitch from mSpy to KrebsOnSecurity in March 2015 stated that approximately 40 percent of the company’s users are parents interested in keeping tabs on their kids. Assuming that is a true statement, it’s ironic that so many parents may now have unwittingly exposed their kids to predators, bullies and other ne’er-do-wells thanks to this latest security debacle at mSpy.

As I wrote in a previous story about mSpy, I hope it’s clear that it is foolhardy to place any trust or confidence in a company whose reason for existence is secretly spying on people. Alas, the only customers who can truly “trust” a company like this are those who don’t care about the privacy and security of the device owner being spied upon.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.