Blind Trust in Email Could Cost You Your Home

Google parent Alphabet’s revenue rises 22.2 percent

April 27, 2017Microsoft’s quarterly revenue falls short of estimates

April 27, 2017The process of buying or selling a home can be extremely stressful and complex, but imagine the stress that would boil up if — at settlement — your money was wired to scammers in another country instead of to the settlement firm or escrow company. Here’s the story about a phishing email that cost a couple their home and left them scrambling for months to recover hundreds of thousands in cash that went missing.

It was late November 2016, and Jon and Dorothy Little were all set to close on a $200,000 home in Hendersonville, North Carolina. Just prior to the closing date on Dec. 2 their realtor sent an email to the Little’s and to the law firm handling the closing, asking the settlement firm for instructions on wiring the money to an escrow account.

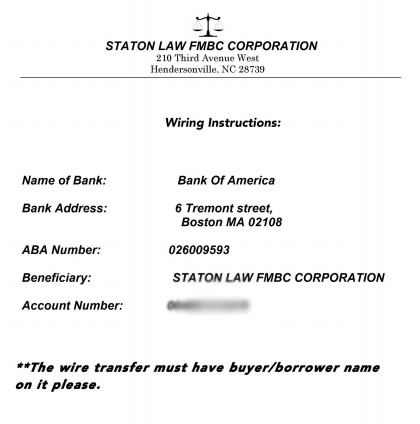

The fraudulent wire instructions apparently sent by the hackers via the settlement law firm.

An attorney with the closing firm responded with wiring instructions as requested, attaching a document that had the law firm’s logo and some bank account information that was represented as the seller’s account number. The Little’s realtor sent the wire on Thursday morning, the day before settlement.

“We went to closing at 1 p.m. on Friday, and after we signed all the papers, we asked the lawyers if we were going to get back the extra money we had sent them, because they hadn’t be able to give us an exact amount in the wiring instructions. At that point they told us they had never gotten the money.”

After some disagreement, both legitimate parties to the transaction agreed that someone’s email had been hacked by the fraudsters, and was used to divert the wired funds to an account the criminals controlled. The hackers had forged a copy of the law firm’s letterhead, and beneath it placed their own Bank of America account information (see screen shot above).

The owner of the Bank of America account appears to have been a willing or unwitting accomplice — also know as a “money mule” — recruited through work-at-home job schemes to receive and forward funds stolen from hacked business accounts. In this case, the money mule wired all but 10 percent of the money (a typical money mule commission) to an account at TD Bank.

Fortunately for the Littles, the FBI succeeded in having the resulting $180,000 wire transfer frozen once it hit the TD Bank account. However, efforts to recover the stolen funds were stymied immediately when the Littles’ credit union refused to give Bank of America a so-called “hold harmless” agreement that the bigger bank wanted as a legal guarantee before agreeing to help.

Charisse Castagnoli, an adjunct professor of law at the John Marshall Law School, said banks have a fiduciary duty to their customers to honor their requests in good faith, and as such they tend to be very nervous legally about colluding with another bank to reverse payment instructions by one of their own customers. The “hold harmless” agreement is usually sought by the bank which received a fraudulent wire transfer, Castagnoli said, and it requires the responding bank to assume any and all liability for costs that the requesting bank may later incur should the owner of account which received the fraudulent wire decide to dispute the payment reversal.

“When it comes to wire fraud cases the banks have to move very quickly because once the wires make it outside the U.S. to foreign banks, the money is usually as good as gone,” Castagnoli said. “The receiver or transferee usually insists on a hold harmless agreement because they’re moving the money on behalf of their own account holder, kind of going against their own client which is a big ‘no-no’ when you’re a fiduciary.”

But in this case, the credit union in which the Littles had invested virtually all of their money for more than 40 years decided it could not in good faith provide that hold harmless agreement, because doing so would stipulate that the credit union affirms the victim (the Littles) hadn’t willingly and knowing initiated the wire, when in fact they had.

“I talked to the wire dept multiple times,” Mr. Little said of the folks at his financial institution, Atlanta, Ga.-based Delta Community Credit Union (DCCU). “They finally put me through to the vice president of loss prevention at the credit union. I’m not sure they even believed all that was going on. They finally came back and told me they couldn’t do it. Their rules would not allow them to send a hold harmless letter because I had asked them to do something and they had done it. They had a big meeting last week with apparently the CEO of the credit union and several other people. Then they called me on Monday again and told me they would not could not do it.”

The Littles had to cancel the contract on the house they were prepared to occupy in December. Most of their cash was tied up in this account that the banks were haggling over, and so they opted to get a heavily mortgaged small townhome instead, with the intention of paying off the mortgage when their stolen funds are returned.

“We canceled the contract on the house because the sellers really needed to sell it,” Jon Little said.

The DCCU has yet to respond to my requests for comment. But less than a day after KrebsOnSecurity reached out to the credit union for comment about the Littles’ story, the bank informed the Littles that the other bank would soon have its hold harmless letter — freeing up their $180,000 after more than four months in legal limbo.

The Littles’ story has a fairly happy ending, however most of the other few dozens stories previously featured on this blog about wayward mortgage, escrow and payroll payments wound up with the victim losing six figures at least.

One of the more recent advertisers on this blog — Ninjio — specializes in developing custom, “gamified” security awareness training videos for clients. “The Homeless Homebuyer,” one of the videos Ninjio produced for a government client seems appropriate here: It features an animated FBI agent breaking the bad news to some would-be homeowners that their money is gone and so are their dreams of a new home — all because everyone blindly trusted unsecured email for what is essentially a high-risk cash transaction.

I like the video because its message is fairly stark and real: You could get screwed if you don’t take this seriously and proceed carefully, because once the money’s gone it usually stays gone. Check it out here:

[embedded content]

So here’s what you need to know if you or anyone you know, love or even like are about to buy or sell a home: Never wire money based on the say-so of one party to the transaction made via email. You simply don’t know if their account is hacked, so from a self-preservation standpoint it’s best to assume it is.

Agree in advance who will contact whom — preferably by phone — on settlement day to receive the wiring details, and who will manage the wiring process. Never trust bank account details and payment instructions sent via email. Always double or even triple check any instructions for wiring money at settlement. Confirm all wiring instructions in person if possible, or else over the phone.

By the way, these same precautions can help make organizations less susceptible to CEO fraud schemes, email scams in which the attacker spoofs the boss and tricks an employee at the organization into wiring funds to the fraudster.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has been keeping a running tally of the financial devastation visited on companies via CEO fraud scams. In June 2016, the FBI estimated that crooks had stolen nearly $3.1 billion from more than 22,000 victims of these wire fraud schemes.

Castagnoli said many credit unions and small banks don’t have the legal staff with the clearance to make calls on whether to issue a hold harmless agreement, and so they usually try to punt on that when requested. Were she in The Littles’ position, Castagnoli said she would have called the head of the credit union and demanded assistance.

“If the head of the bank wouldn’t do it, I’d call my congressperson or a state banking regulator,” she said.

If you’re selling or buying the home yourself and somehow also in charge of wiring money, consider using a Live CD approach (all of these “live” Linux distributions will just as happily run on USB-based flash drives). I have long recommend Live Linux usage as a smart option for small businesses to avoid paying dearly when a Windows banking trojan snarfs their business banking credentials.

Tags: Bank of America, Charisse Castagnoli, Delta Community Credit Union, Dorothy Little, fbi, Jon Little, TD Bank