Data: E-Retail Hacks More Lucrative Than Ever

FireEye second-quarter profit, revenue forecast miss estimates

April 30, 2019Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt to step down from board

April 30, 2019For many years and until quite recently, credit card data stolen from online merchants has been worth far less in the cybercrime underground than cards pilfered from hacked brick-and-mortar stores. But new data suggests that over the past year, the economics of supply-and-demand have helped to double the average price fetched by card-not-present data, meaning cybercrooks now have far more incentive than ever to target e-commerce stores.

Traditionally, the average price for card data nabbed from online retailers — referred to in the underground as “CVVs” — has ranged somewhere between $2 and $8 per account. CVVs are are almost exclusively purchased by criminals looking to make unauthorized purchases at online stores, a form of thievery known as “card not present” fraud.

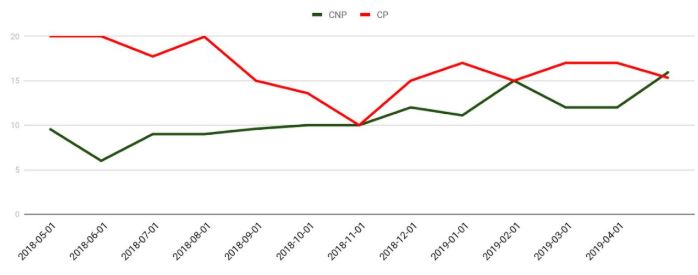

In contrast, the value of “dumps” — hacker slang for card data swiped from compromised retail stores, hotels and restaurants with the help of malware installed on point-of-sale systems — has long hovered around $15-$20 per card. Dumps allow street thieves to create physical clones of debit and credit cards, which are then used to perpetrate so-called “card present” fraud at brick and mortar stores.

But according to Gemini Advisory, a New York-based company that works with financial institutions to monitor dozens of underground markets trafficking in both types of data, over the past year the demand for CVVs has far outstripped supply, bringing prices for both CVVs and dumps roughly in line with each other.

Stas Alforov, director of research and development at Gemini, says his company is currently monitoring 55 underground stores that peddle stolen card data — including such heavy hitters as Joker’s Stash, Trump’s Dumps, and BriansDump.

Contrary to popular belief, when these shops sell a CVV or dump, that record is then removed from the inventory of items for sale, allowing companies that track such activity to determine roughly how many new cards are put up for sale and how many have sold. Underground markets that do otherwise quickly earn a reputation among criminals for selling unreliable card data and are soon forced out of business.

“We can see in pretty much real-time what’s being sold and which marketplaces are the most active or have the highest number of records and where the bad guys shop the most,” Alforov said. “The biggest trend we’ve seen recently is there appears to be a much greater demand than there is supply of card not present data being uploaded to these markets.”

Alforov said dumps are still way ahead in terms of the overall number of compromised records for sale. For example, over the past year Gemini has seen some 66 million new dumps show up on underground markets, and roughly half as many CVVs.

“The demand for card not present data remains strong while the supply is not as great as the bad guys need it to be, which means prices have been steadily going up,” Alforov said. “A lot of the bad guys who used to do card present fraud are now shifting to card-not-present fraud.”

One likely reason for that shift is the United States is the last of the G20 nations to make the transition to more secure chip-based payment cards, which is slowly making it more difficult and expensive for thieves to turn dumps into cold hard cash. This same increase in card-not-present fraud has occurred in virtually every other country that long ago made the chip card transition, including Australia, Canada, France and the United Kingdom.

The increasing value of CVV data may help explain why we’ve seen such a huge uptick over the past year in e-commerce sites getting hacked. In a typical online retailer intrusion, the attackers will use vulnerabilities in content management systems, shopping cart software, or third-party hosted scripts to upload malicious code that snarfs customer payment details directly from the site before it can be encrypted and sent to card processors.

Research released last year by Thales eSecurity found that 50 percent of all medium and large online retailers it surveyed acknowledged they’d been hacked. That figure was more than two and a half times higher than a year earlier.

BIG BANG VS. LOW-AND-SLOW

Much of the media’s attention has been focused on recent hacks against larger online retailers, such those at the Web sites of British Airways, Ticketmaster, and electronics giant NewEgg. But these incidents tend to overshadow a great number of “low-and-slow” compromises at much smaller online retailers — which often take far longer to realize they’ve been hacked.

For example, in March 2019 an analysis of Gemini’s data strongly suggested that criminals had compromised Ticketstorm.com, an Oklahoma-based business that sells tickets to a range of sporting events and concerts. Going back many months through its data, Gemini determined that the site has likely been hacked for more than two years — allowing intruders to extract around 4,000 CVVs from the site’s customers each month, and approximately 35,000 accounts in total since February 2017.

Ticketstorm.com did not respond to requests for comment, but an individual at the company who answered a call from KrebsOnSecurity confirmed Ticketstorm had recently heard from Gemini and from card fraud investigators with the U.S. Secret Service.

“It’s not just large sites getting popped, it’s mostly small to mid-sized organizations that are being compromised for long periods of time,” Alforov said. “Ticketstorm is just one of ten or twenty different breaches we’ve seen where the fraudsters sell what they collected and then come back and collect more over several years.”

In some ways, CVVs are more versatile for fraudsters than dumps. That’s because about 90 percent of dumps for sale in the underground do not come with other consumer data points needed to complete a various online transactions — such as the cardholder’s name or billing address, Gemini found.

This is particularly true when CVV data is collected or amended by phishing sites, which often ask unwitting consumers to give up other personal information that can aid in identity theft and new account fraud — including Social Security number, date of birth and mother’s maiden name.

All of which means e-commerce retailers need to be stepping up their game when it comes to staving off card thieves. This in-depth report from payment security firm Trustwave contains a number of useful suggestions that sites can consider for a defense-in-depth approach to combating an increasingly crowded field of criminal groups turning more of their attention toward stealing CVV data.

“There is a lot more incentive now than ever before for thieves to compromise e-commerce sites,” Alforov said.